Member states of the UN Human Rights Council – the leading international forum for the promotion and protection of human rights – have a special responsibility to uphold human rights standards. Nevertheless, evidence suggests that Council members have worse human rights records than the global average. This article discusses how the growing influence of repressive states in the Human Rights Council may weaken international human rights norms.

When the UN Human Rights Council (HRC) was established in 2006, replacing the UN Commission on Human Rights, then U.S. Ambassador to the UN John Bolton declared: “We want a butterfly. We’re not going to put lipstick on a caterpillar and declare it a success.” The UN Commission on Human Rights was abandoned amid concerns about the appalling human rights records of several of its member countries and widespread politicization. High expectations were placed on the new HRC to be a more human rights friendly forum. Has the HRC lived up to these expectations, and do its members, who are supposed to promote human rights norms around the globe, respect human rights themselves?

The HRC Member State Election Process

The HRC is composed of 47 member states elected by a majority vote of the UN General Assembly for three-year terms. Seats on the HRC are allocated on the basis of an equitable geographical distribution such that each region of the world is adequately represented. The General Assembly resolution that established the HRC explicitly calls on states to consider a state’s “contribution to the promotion and protection of human rights” when electing members to the Council. Hence, the 47 member states of the HRC should, in principle, be states that are committed to human rights norms, which implies that they should respect the human rights of their citizens.

Empirical Evidence on the Human Rights Records of HRC Member States

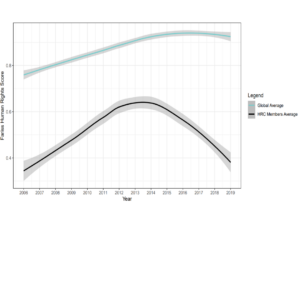

Are HRC member states champions of human rights? To analyze this claim, I use Fariss Human Rights Scores, which provide an annual measure of the level of respect for human rights in each state in the world, based on a variety of information sources provided by national and international human rights organizations. Fariss Human Rights Scores are widely considered to be the most accurate measure of states’ human rights records because they take into account that both the capacity to report human rights violations and our understanding of what constitutes human rights violations have changed over time. For each year since the inception of the HRC, I calculated the average Fariss Human Rights Score of the 47 HRC members and the global average.

Figure 1: Human Rights Records Over Time (HRC Members vs. Global Average)

Source: Original data analysis by the author based on data provided by Fariss (2020)

Figure 1 compares the average Fariss Human Rights Scores of the 47 HRC members with the global average over time. The figure shows that, on average, HRC member states have lower Fariss Human Rights Scores than the global average, which means that they violate human rights more frequently. Moreover, the figure shows that there is a time trend toward higher levels of human rights violations among HRC member states, that began around 2014. This means that over time it has become more common for highly repressive states to be elected to the HRC by the UN General Assembly.

Consequences for International Human Rights Protection

The question arises to what extent the HRC’s membership composition undermines its ability to promote international human rights norms. Recent events suggest that the growing influence of repressive states in the HRC has a highly detrimental impact. In October 2022, the HRC members rejected a draft decision to hold a debate on human rights violations in China’s Xinjiang region. This occurred despite widespread evidence of crimes against humanity committed by the Chinese authorities against ethnic Uyghurs in Xinjiang. Amnesty International representatives stated that this vote “protects the perpetrators of human rights violations rather than the victims” and “sullies the reputation of the HRC”.

In general, there is a substantial risk that the growing influence of repressive states in the HRC undermines international human rights norms. Research suggests that major autocratic powers such as China or Russia aim to weaken international human rights norms focused on civil and political rights and to abandon any country-specific human rights shaming. They also seek to weaken the influence of civil society organizations in the HRC and promote a culturally relativistic understanding of international human rights norms.

It is essential that the international human rights community is aware of these challenges and prepared to confront them. We must oppose the election of highly repressive states to the HRC, hold them accountable to the principles enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and be vigilant against autocratic attempts to undermine the substance of international human rights norms.