By seeking an electricity agreement with the EU, Switzerland aims to enhance grid integration, support cross-border renewable energy flows, and safeguard security of supply as nuclear power is phased down. However, will this, together with the expansion of domestic renewables, and more energy efficiency, result in a successful energy transition?

When Swiss voters approved the Energy Strategy 2050 in 2017, the roadmap appeared straightforward: expand renewables, improve efficiency, and phase out nuclear power. But what is the reality? In April 2024, the European Court of Human Rights ruled that Switzerland is not doing enough to combat climate change. However, the question is not so much whether the country is doing enough, but rather whether it is taking the right measures.

More than two-thirds of primary energy is imported

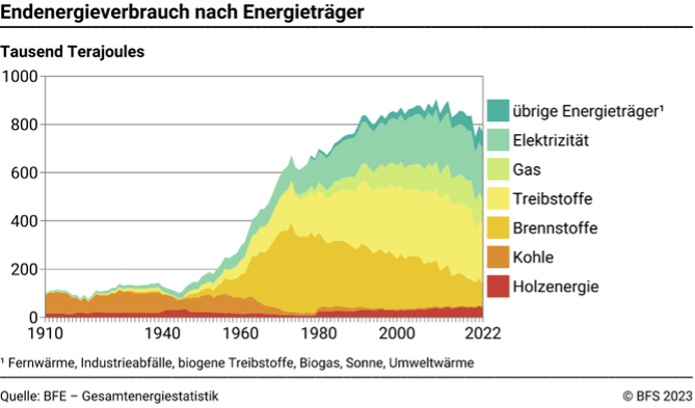

In 2022, Switzerland consumed around 765,000 terajoules (TJ) of primary energy for electricity and heat. Of this, 70 percent was imported.

This primary energy is used for households, services, industry and transport & mobility. While households and services can be transformed relatively easily, the situation is different for industries, transport & mobility because they depend on large amounts of high-quality energy.

The growing electrification gap and why electrification alone won’t be enough

Switzerland has set the ambitious target: a fully carbon-neutral energy supply by 2050. At the heart of this transition lies a massive shift toward green electricity and climate-friendly fuels. Studies from Swiss Association of Electricity Companies (VSE) and a Swiss Research Consortium estimate that the annual electricity demand could surge from 57 TWh in 2022 to anywhere between 75 and 90 TWh by 2050. This includes the replacement of 23 TWh, currently produced by nuclearpower plants, which are planned to be phased out in future, and that makes the situation even more challenging.

Covering the future electricity demand would require a massive build-out of domestic renewables. Yet even these resources have limits, as a closer look reveals. Switzerland’s new Energy Act calls for 45 TWh of renewable power by 2050 but hitting that target with photovoltaics would mean carpeting roughly 225 square kilometers with photovoltaic panels. That’s the equivalent of more than 30,000 football fields. However, an EPFL/ETH analysis estimates that rooftop solar, even with ambitious but realistic deployment, could only supply around 24 TWh annually. The remaining gap would need to be filled by wind farms and biomass facilities. The takeaway is clear: while electrification powered by domestic renewables is a cornerstone of Switzerland’s climate strategy, it cannot shoulder the entire energy transition on its own.

Can the European electricity market solve the problem?

Switzerland’s integration into the European electricity grid remains strategically vital. Yet relying on imports for closing electricity gaps is far from guaranteed. Neighboring countries, such as Germany – now phasing out both nuclear and coal – and France, with its heavy dependence on aging nuclear plants, are grappling with energy challenges of their own. In such a landscape, expecting uninterrupted import security at all times becomes increasingly difficult.

How about better energy efficiency?

The potential for squeezing out major new gains in energy efficiency is limited. Since the 1990s, Switzerland – especially its industrial sector – has already made substantial strides, driven in part by the pressure to stay competitive on the global stage. Any further improvements are still possible, but they will come with relatively hefty investment costs.

So what now?

For Switzerland to move forward, it must acknowledge a hard truth: the slow pace of the energy transition is not just a failure of political will, it reflects the sheer complexity of the task. We simply cannot expect to build our low-carbon future using the same blueprint that shaped its current energy system.

What lies ahead is nothing short of a profound transformation, one that touches every layer of society. A credible long-term strategy will likely require a balanced and diverse energy mix, plus a human behavioral shift towards more mindful energy use. Only then can the country design a resilient and credible long-term low carbon strategy.