The United Nations (UN) human rights division depends on the information and testimony of human rights defenders worldwide. However, human rights defenders frequently encounter retaliatory violence in response to their cooperation with the UN because repressive states aim to deter such collaboration. This blogpost highlights the global scale of this issue and discusses strategies to minimize the risk of state reprisals.

Civil society activists from the NGO Human Rights Center Viasna were subject to raids, arbitrary arrests, and criminal charges following their intensified cooperation with the UN human rights section. Similarly, human rights defenders from the Saudi Association of Civil and Political Rights faced imprisonments and travel bans for allegedly providing « false information » to the UN Special Procedures. In another case, human rights lawyers in Yemen were intimidated and harassed for sharing information with the UN and other international organizations.

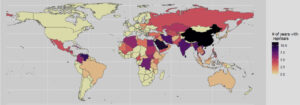

Unfortunately, these cases of state violence in response to acts of cooperation with the UN are not isolated examples, but rather illustrate of a profound global problem. The UN Secretary-General publishes an annual report on cases of state reprisals for cooperation with the UN. This report lists all states where there is evidence that human rights defenders have faced retaliation in response to their involvement with the UN. Figure 1 shows how often each state was mentioned in these UN reprisal reports over the period from 2010 to 2023. The world map illustrates that state reprisals in response to cooperation with the UN have occurred in various countries, and that the issue is especially profound in China and Saudi Arabia.

Figure 1: Global distribution of reprisals for cooperation with the UN (2010-2023)

Source: Original data analysis based on data provided by the UN Secretary-General

While this evidence already suggests that state reprisals are a major global concern, it is important to emphasize that the reprisal cases reported by the UN Secretary-General represent only a subset of the actual number of reprisal cases. First, there is likely to be a huge dark figure of state reprisals that occur outside the international spotlight, which do not appear in the reprisal report. Second, the UN Secretary-General is committed to « do no harm » principles and therefore only reports on cases of reprisals when the risk of further reprisals in response to inclusion in the report is limited. Thus, the UN reprisal reports reveal only the tip of the iceberg of the actual number of cases of state reprisals for cooperation with the UN.

As a result of such reprisals, human rights defenders may be increasingly intimidated from cooperating with the UN. To the extent that human rights defenders are deterred from providing information to the UN, repressive states may be able to commit human rights violations in secret without facing international accountability. Hence, state reprisals threaten the core mission of the UN human rights section, and it is of the utmost importance to address this issue and develop effective safeguards.

In light of the complexity of the problem, this article can only make a few suggestions, but hopes to stimulate a broader debate. First, the UN should strengthen access points for filing anonymous complaints about human rights violations. Given the pervasive risk of state reprisals, it is of great concern that public UN communications that follow up on individual complaints contain personal information about victims of human rights violations including their names. To protect the anonymity of human rights defenders, the UN should not only anonymize these documents but also encrypt all online contact forms to prevent repressive states from intercepting sensitive information.

Second, the UN should strengthen its follow-up mechanisms to monitor the situation of human rights defenders after their cooperation with the UN. Ideally, the UN would establish follow-up mechanisms along the lines of national witness programs for human rights defenders who have provided information to the UN. Third, the UN must strengthen its focal points on reprisals and improve cooperation with civil society actors and national governments to ensure a coordinated, effective, and timely response to state reprisals. The UN should also advance policy instruments such as the San José Guidelines against Intimidation and Reprisals, whose scope is currently limited to states that have ratified international human rights treaties. Overall, the UN member states need to invest greater resources to address the issue of state reprisals. This would be a worthwhile investment, because only if human rights defenders can freely and safely access and communicate with the UN will it be possible for the UN human rights division to truly fulfill its mandate.