Iran is facing one of the most violent outbreaks of COVID-19 worldwide. The ability of its health system to fight back has been hampered by the dire economic situation in the country and its limited ability to purchase medical equipment on the international markets. Both are at least partially due to the comprehensive sanctions targeting the country, reminding public and decision-makers alike of an old truth: international sanctions kill.

Iran has so far suffered more than 2,234 deaths due to the Coronavirus, surpassed only by China, Italy and Spain, and reported more than 29,406 positive cases. And yet the US administration has declined to adapt its sanction regime to ease the burden on the Iranian people, despite the calls from both the Iranian leadership and the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, as well as a US presidential candidate. The administration even doubled down on its ‘maximum pressure’ strategy by backlisting five new companies accused of exporting Iranian oil.

As explained in a previous blogpost, while most sanctions imposed on Iran linked to its nuclear program were lifted following the signature of the JCPOA in 2015, the Trump administration decided in 2018 to withdraw from the latter and to reimpose comprehensive sanctions on Iran. The extraterritoriality of US sanctions, combined with the centrality of the US market and US Dollar in the global economy, de facto means that the US sanctions hamper trade with Iran for almost any entity or country around the world. That is especially true for European economic operators due to the high-level of transatlantic economic integration.

The US sanctions imposed on Iran affect its ability to fight the COVID-19 pandemic in at least three ways. First of all, its economy pays a heavy toll, losing almost 10% of real GDP in 2019, which impacts the state’s room for budget spending, notably in public services such as healthcare. Secondly, by directly targeting buyers of Iranian oil and gas, the US sanctions struck the main Iranian source of foreign currencies, restricting Iran’s ability to pay for imports on international markets. Last but not least, sanctions limit the ability of Iran to purchase goods abroad, as exporters are worried to suffer from US prosecution if they continue their dealings with Iran.

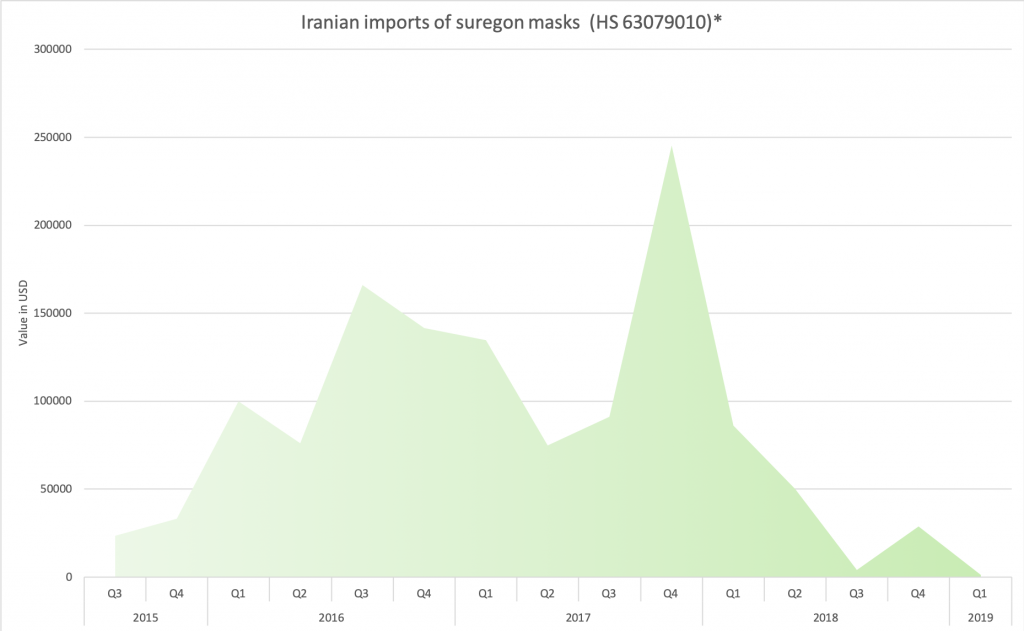

Crucially, Iranian difficulties to acquire foreign goods also entail limited access to medical equipment, as well as medicines and their components. This inability to mass purchase the necessary equipment to face the pandemic did not only arise with the spread of the coronavirus but well before, therefore affecting its ability to stockpile medical equipment needed in case of such outbreaks. Already in October 2019, Human Rights Watch accused US sanctionsof posing a «serious threat to Iranian’s right to health and access to essential medicines». For instance, Iranian imports of surgeon masks, crucial to preventing contamination of medical staff, illustrate perfectly the impact of sanctions on Iranian health capabilities. Imports boomed after the lifting of nuclear-related sanctions in 2015, before drastically diminishing after the reimposition of sanctions by the Trump administration, leaving the country ill-prepared for the COVID-19 pandemic.

In order to understand the Iranian difficulties, one needs to analyse how the exterritoriality of US sanctions impacts the decision-making of economic operators around the world. On paper, humanitarian goods such as medicine or food are exempted from the sanctions imposed on Iran by the US Treasury. Likewise, the European Union’s blocking statute is supposed to protect EU operators from the reach of US sanctions. Nevertheless, the aggressive implementation of US sanctions creates uncertainty for economic operators, which risk important compliance fines or exclusion from the US market, discouraging most of them to even engage in nominally «licit trade» with Iran. In addition, US pressure on SWIFT, the central nervous system of international financial transactions but nominally a private entity under Belgian jurisdiction, forced it to cut off Iranian banks’ access to cross-border payments which, added to the direct sanctioning of the Central Bank of Iran, made trading with Iran increasingly complicated, even for operators ready to take the risk. In reality, international organisations, partially funded by the US, have suffered from difficulties of transferring the necessary goods and capital to run their programs in Iran.

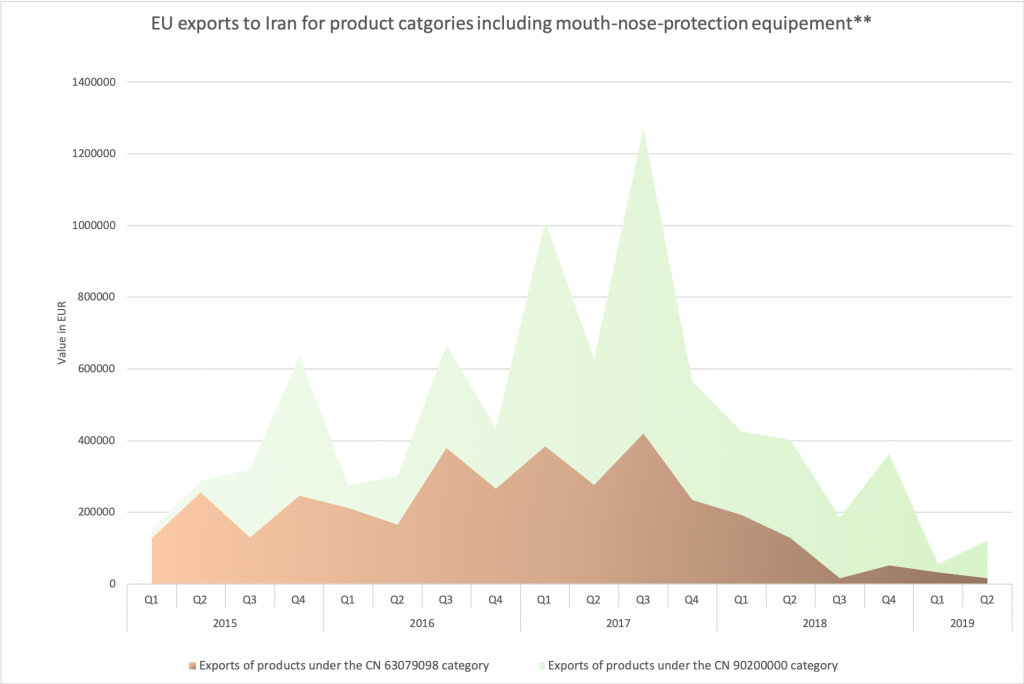

Although ‘dedicated vehicles’ were set up in order to provide safe means of conducting licit trade with Iran, such as the European INSTEX or the Swiss SHTA, they have yet to produce any transactions. In addition, the recent decision of the European Commission to restrict the exports of protective equipment due to the shortage experienced by some of its member states might appear like bad news for Iran. In reality, the EU exports of some of those products to Iran have been falling dramatically since 2017, and this despite the EU having lifted its trade restrictions against Iran and refusing to recognize the US jurisdiction on EU operators. For instance, categories of exports encompassing mouth-nose-protection equipment, which augmented significantly after the lift of sanctions in 2015, have fallen by close to 90% between the first half of 2017 and the first half of 2019, following the reimposition of US sanctions.

As such, the COIVD-19 crisis in Iran has underlined an old truth: comprehensive international sanctions not only hurt the targeted regime but also the civilian population. By design, they intend to create economic pain in the hope of provoking political gains. In that sense, the debate on US sanctions against Iran is echoing the one surrounding the UN sanctions imposed against Saddam Hussein’s Iraq in the 90s, which have been accused of resulting in as much as half a million child deaths. Far from being a benign way to showcase moral outrage or ideological opposition, international sanctions are violent foreign policy tools and therefore should be drafted and used carefully.

Cover picture by frank mckenna retrieved on Unsplash

*Data retrieved from Global Trade Tracker (reporter Iran), based on data from Iranian customs.

** Data retrieved from Global Trade Tracker (reporter EU, including UK), based on data from national customs.